By: Gautam Narula

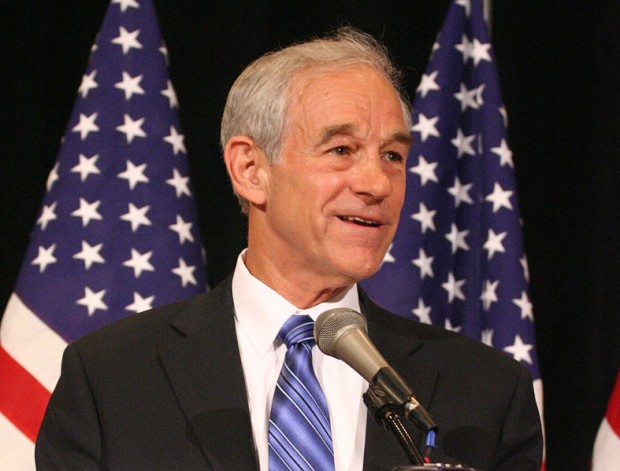

Ron Paul is no stranger to a presidential campaign. He ran for president as a Libertarian in 1988 and a Republican in 2008 and 2012. In 1988, he received less than .5 percent of the vote. In 2008, in the Republican primary, his numbers hovered in the 4-5 percent range. However, in 2012, his campaign ignited. He polled nearly twice as high in the primaries and was embraced by an enthusiastic crowd of young supporters. Even when it became clear that Mitt Romney would be the Republican nominee, Paul’s zealous supporters were still scheming to use the delegates process to take the nomination. And Paul, virtually ignored by the Republican establishment in the past, was sent off with a four minute tribute video where he was praised and celebrated by the leaders of the very same establishment.

Ron Paul is no stranger to a presidential campaign. He ran for president as a Libertarian in 1988 and a Republican in 2008 and 2012. In 1988, he received less than .5 percent of the vote. In 2008, in the Republican primary, his numbers hovered in the 4-5 percent range. However, in 2012, his campaign ignited. He polled nearly twice as high in the primaries and was embraced by an enthusiastic crowd of young supporters. Even when it became clear that Mitt Romney would be the Republican nominee, Paul’s zealous supporters were still scheming to use the delegates process to take the nomination. And Paul, virtually ignored by the Republican establishment in the past, was sent off with a four minute tribute video where he was praised and celebrated by the leaders of the very same establishment.

Paul’s surge in support among the young is no surprise. A recent Reason poll showed that 61 percent of young voters would choose a socially liberal, fiscally conservative candidate. In the past two decades, polling by CNN has shown a marked increase of the proportion of Americans who subscribe to libertarian viewpoints. Ron Paul’s increasing popularity has been awkward for the Republican Party: his supporters are often the most vocal critics of mainstream Republicans, and his ideology runs counter to much of the party’s stated platform. His rise highlights the paradox characterizing the core of modern conservatism. Although the Republican Party champions itself as the party of small government, it is fueled by broad coalitions that seek to increase the size and power of government.

The best known big government Republican coalition is social conservatism, embodied in candidates like Rick Santorum. Social conservatives see government as a societal enforcer of morality. To this end, social conservatives want to expand government power to increase the role of religion in public life (for instance, with prayer in public schools) and use it to prevent gay marriage, abortions, pornography, drug legalization, and other actions they feel undermine society’s traditional values, overriding the views of individual states if necessary. The second big government force is the militaristic wing of the Republican Party. This faction wants a large, robust military—and hence, a large, robust defense budget—and is more open to abrogating civil liberties in favor of enhanced military power, as in the cases of Guantanamo Bay, wiretapping by the National Security Agency, and the use of torture or “enhanced interrogation techniques”. The big government Republicans were most visible under the administration of George W. Bush, when his expansion of Medicare, increase of the federal government’s role in education, and deficit spending met little opposition from Republicans in Congress.

This leads to the question: why do libertarians associate with the Republican Party when much of their ideology is fundamentally at odds with the Republican mainstream? Ron Paul ran as a Republican, as did Gary Johnson before he dropped out to run as a Libertarian. The Koch brothers, the libertarian oil magnates who have spoken in favor of gay marriage, marijuana legalization, and reduced military spending, are expected to spend nearly half a billion dollars trying to oust Barack Obama. Polls show the majority of prospective libertarian voters, eliminating the choice to vote for Gary Johnson, would vote for Mitt Romney. When the third axis of libertarianism is reduced to the two dimensional scale of Republican and Democrat, the Republicans tend to win out.

But the question remains—why? Historically, libertarianism has found its roots in the Republican Party. Barry Goldwater, often called the founder of modern conservatism, was himself a strong libertarian. Although he believed in a powerful, militaristic America to take on the challenges of the Cold War, he became a vocal critic of the the growth of the religious right and social conservatives, forcefully opposing them on issues of abortion, gay rights, drug legalization, and religion in public life. And perhaps, philosophically, libertarians view social liberalism differently than liberals do. For liberals, social liberalism is a movement to seek equality and opportunity for historically persecuted or disadvantaged groups—to that extent, it is an activist movement. From a libertarian perspective, social issues tend to fall under a larger umbrella of small government, where social liberalism is part of a passive freedom of choice untouched by government. Indeed, libertarians are most vocal when it comes to reducing spending and taxes. For the end goal of smaller government and reductions in spending, an alliance with the Republicans is more promising than the social liberals of the Democratic Party.

What does this mean for the next four years? In truth, not much. The number of economically conservative, socially liberal voters is still too small to bridge the gap between two increasingly polarized parties. The Republican Party cannot accommodate libertarian voters without alienating powerful and well funded religious and social conservative groups. But considering Ron Paul’s popularity among youth and his increasing appeal to the general electorate, Republicans and Democrats alike may one day have to face the fact that libertarianism is here to stay.